Digital twin of a mountainside. AI generated illustration.

Digital twin of a mountainside. AI generated illustration.

The Buzzword Trap

In the infrastructure and construction sectors, digital twin is a term thrown around constantly. But are we falling into a buzzword trap? Are the systems we see today genuinely intelligent twins, or are they just glorified 3D models?

Such models look impressive on a screen, but the critical question remains: Do they have operational value? Is the cost justifiable if we cannot trust the data 100%?

Most importantly, when dealing with geohazards, can we actually prevent a landslide with a data model, or are we simply visualizing the disaster in higher resolution?

What is a Digital Twin, Really?

To answer the previous questions, we must first agree on a definition.

“A digital twin is a virtual representation of a physical system used for real-time monitoring, prediction, and optimization throughout the system’s lifecycle.”

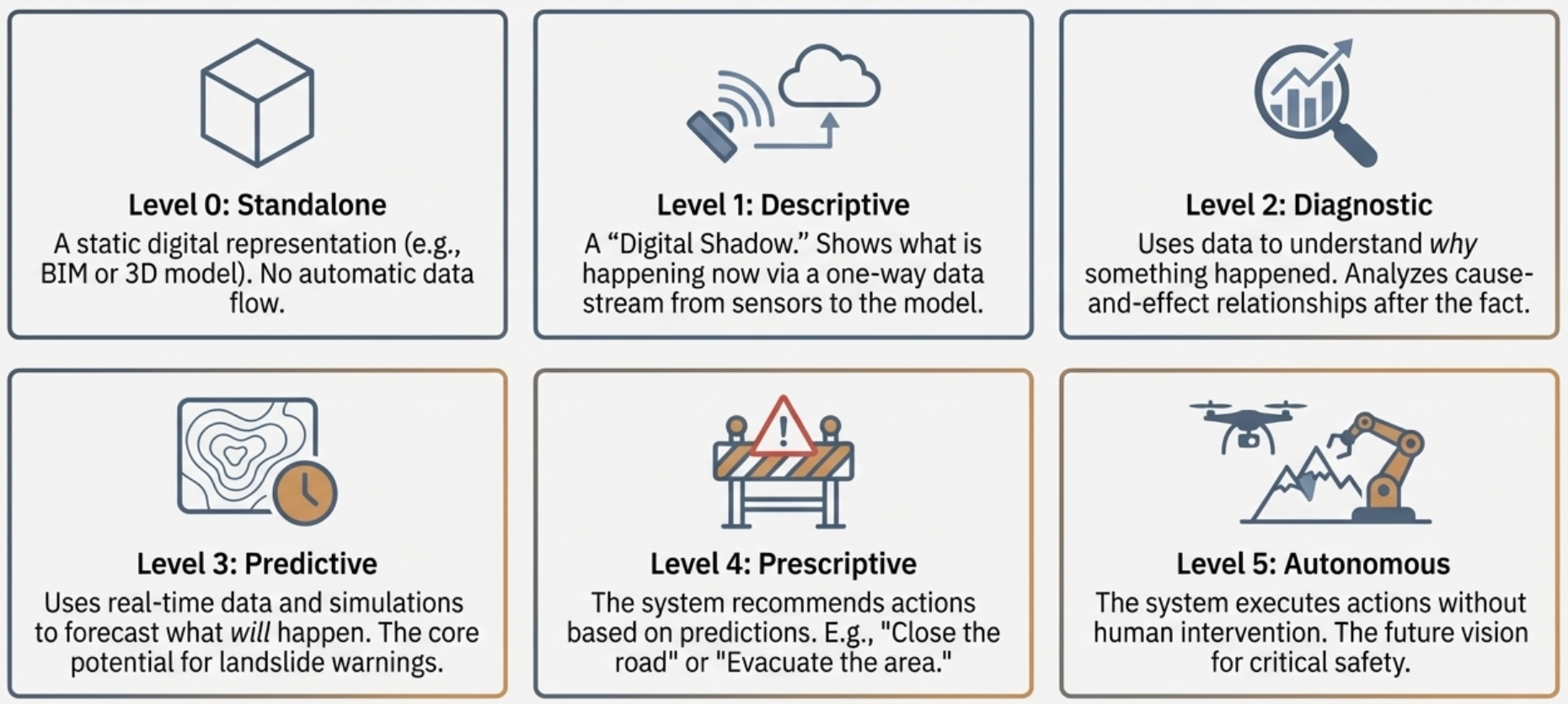

However, not all digital twins are created equal. We can view this through a Digital Twin Maturity Model, illustrated in the figure below:

Maturity level of digital twins, based on San et. al. 2021.

Maturity level of digital twins, based on San et. al. 2021.

Level 3 is where the potential for landslide warning lies, but it is also where we hit a massive wall.

The Nature Gap: Why Industry 4.0 Logic Fails in Nature

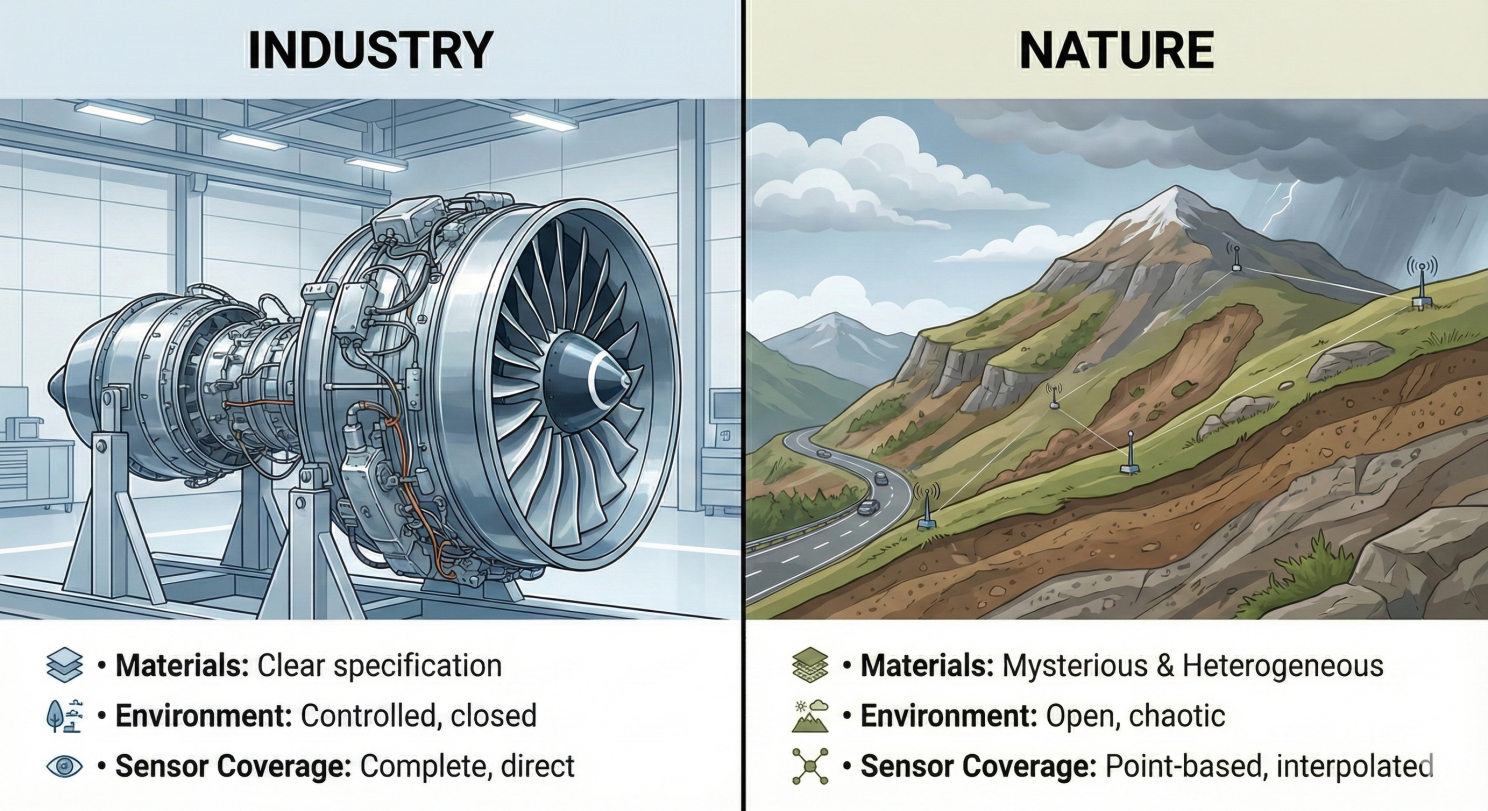

Most success stories about digital twins come from Industry 4.0, like monitoring an industrial machine in real-time via its digital twin. But there is a fundamental difference between a machine and a mountainside. The leap from Diagnostic (Level 2) to Predictive (Level 3) is uniquely difficult in nature for three main reasons:

1) Materials: Specification vs. Mystery - In industry, we know exactly what we built. The steel has a known strength; the parts are standardized. In nature, the ground is heterogeneous and full of surprises. We rarely know exactly what hides between our boreholes.

2) The Environment: Control vs. Chaos - Industrial processes often occur in closed, controlled environments. A mountainside is an open system, battered by uncontrollable external forces, such as extreme rainfall.

3) Sensor Coverage: Complete vs. Point-based - You can measure pressure, temperature or any other parameter at almost every critical point in a machine. We cannot instrument an entire mountain. We measure at a few points and must guess (interpolate) the rest.

Main reasons why digital twins in nature are more challenging than in industrial applications. AI generated illustration.

Main reasons why digital twins in nature are more challenging than in industrial applications. AI generated illustration.

A Further Complication: The Problem of Scale

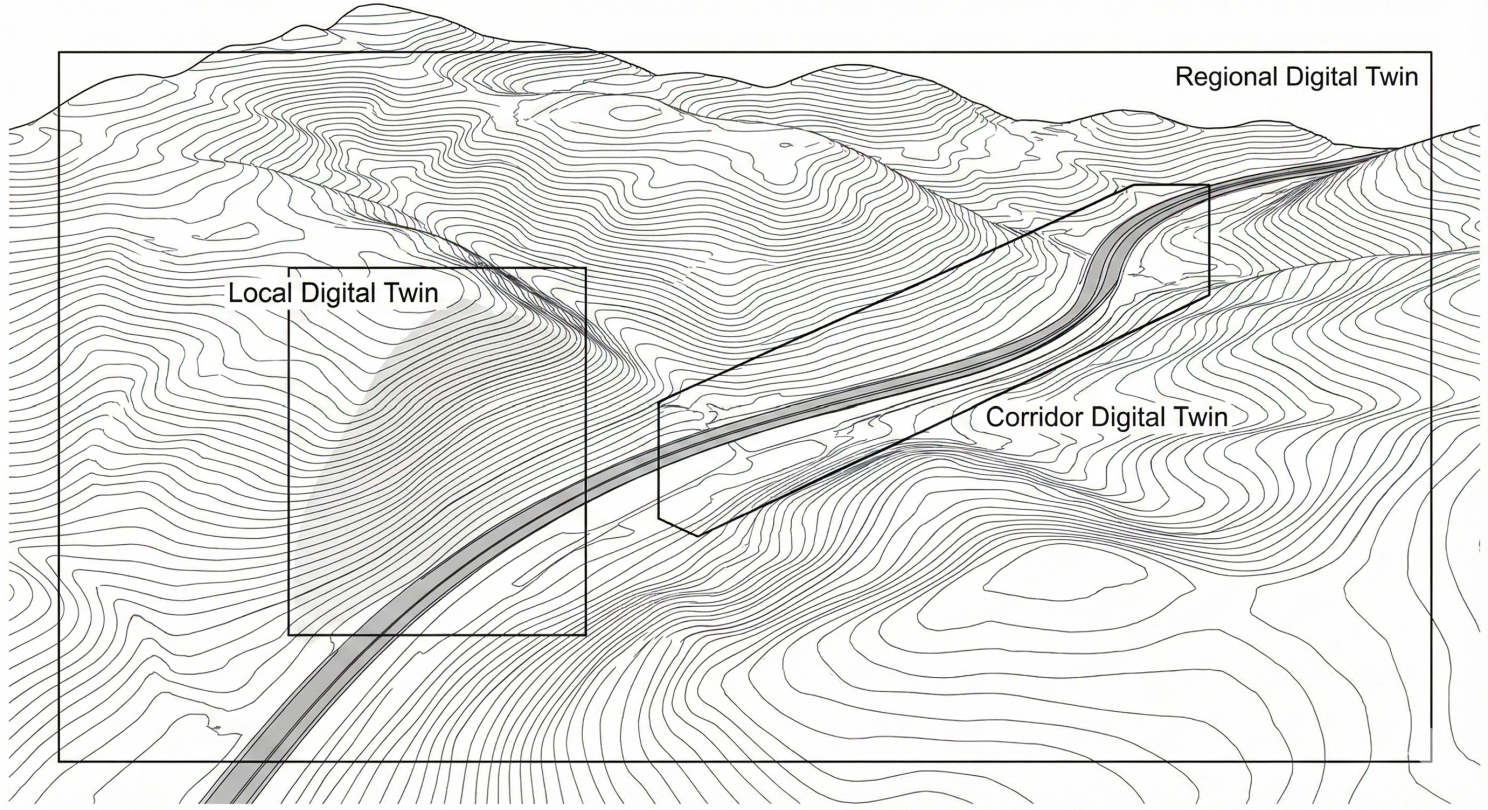

In addition to these challenges in comparison with industrial applications, one size does not fit all when it comes to landslide monitoring. Different operational needs require different types of digital twins. We can categorize digital twins for landslide monitoring into three groups based on the scale of operation:

-

The Local Digital Twin: Focuses on a single critical slope. It uses high-density sensors and detailed geotechnical calculations. The accuracy is high because we seek to understand the physics of that specific location.

-

The Corridor Digital Twin: Focuses on linear infrastructure (e.g., a stretch of road along a major highway). Here, we use hotspot monitoring, instrumenting known risk points and linking them with general topographic, weather and other relevant data.

-

The Regional Digital Twin: Focuses on emergency preparedness for large areas. It primarily relies on remote sensing (Satellite/InSAR) and weather models. A regional digital twin may, for example, be designed as a traffic light system to tell us where to zoom in.

Digital twins of different scales for landslide hazard management. AI generated illustration.

Digital twins of different scales for landslide hazard management. AI generated illustration.

A Pragmatic Solution: The Hybrid AI Engine

How do we bridge the gap and make these reliable? The future lies in a hybrid, layered framework that combines physics with data, and determinism with probability. We need to move toward a funnel approach, especially for corridor and regional digital twins:

-

Regional Scanning: Fast machine learning surrogate models (for example based on physics-informed neural network models) scan the network to provide probabilistic risk assessments.

-

Automated Filtering: High-risk slopes are flagged based on defined thresholds.

-

Site-Specific Analysis: When needed, a full physics-based simulation (FEM) is triggered automatically to calculate a deterministic Factor of Safety (FoS) levels (for cases where there is sufficient and reliable data).

This process is repeated whenever there is new data available. This approach requires effective data utilization strategies than our current limited and scattered usage of data. It is essential to use all relevant data sources (topographical, geological, geotechnical, hydrological, weather, satellite, drone, infrastructure location etc.) in a unified manner. We at SINTEF are actively working towards this goal both through existing projects and new initiatives.

Conclusion: Pipe Dream or Real Possibility?

If we expect a mountainside to behave like a predictable factory machine, a digital twin is a pipe dream. Nature’s chaos cannot be 100% tamed.

However, if we define it as a tool to reduce uncertainty and provide earlier warnings, it is a massive possibility.

The way forward is to accept the uncertainty in the data, embrace hybrid models, and build systems that move us from merely predicting disaster to prescribing action, ultimately supporting better decisions for critical infrastructure and disaster preparedness.

What are your thoughts? Are we ready to trust AI and digital twins with natural hazards?

Originally published on LinkedIn on January 6, 2026.